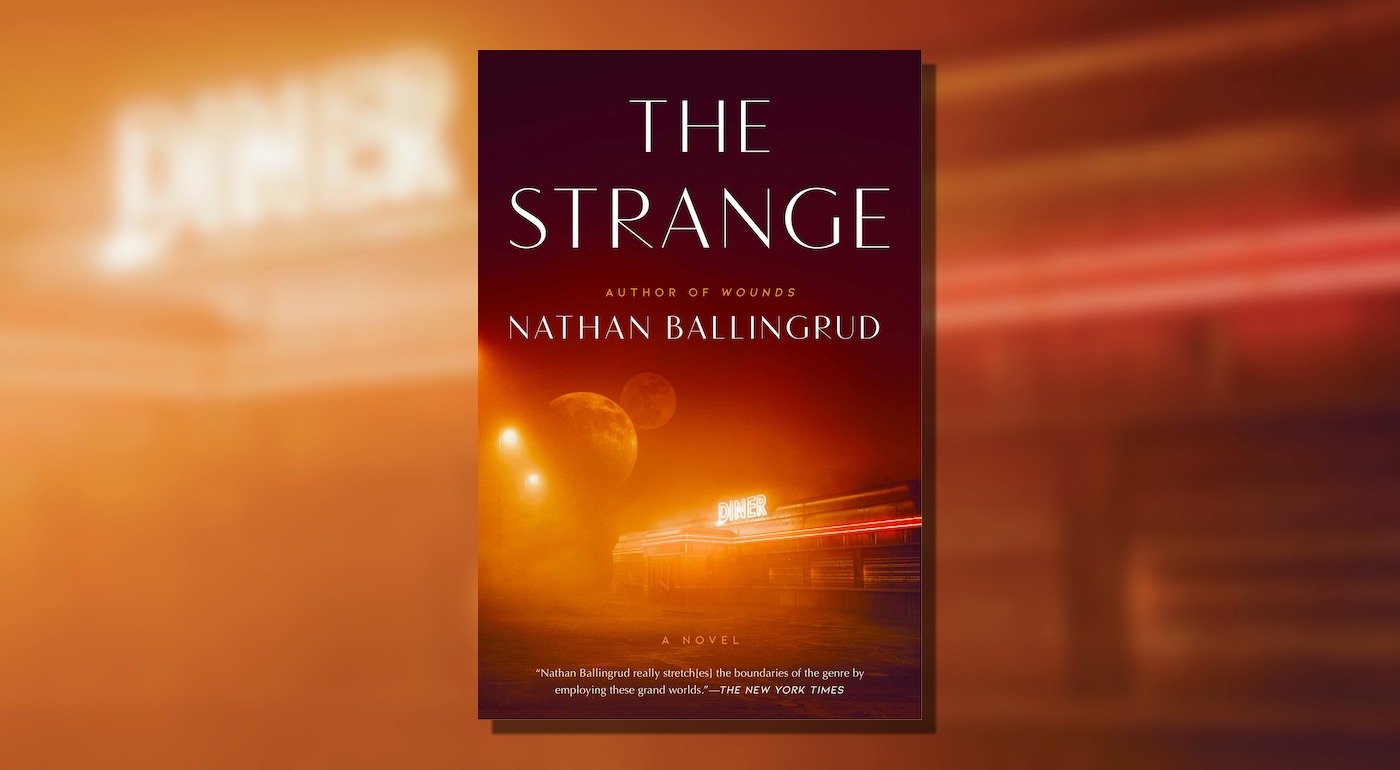

Read an excerpt from Stranger Things

New Galveston, Mars, 1931: 14-year-old Anabelle Crisp sets off across the wastelands of a strange planet…

We’re excited to share with you excerpts from Nathan Ballingrud’s Strange Incident, the story of a girl’s quest for revenge in a weary and angry world, published March 21 by Saga Press.

New Galveston, Mars, 1931: 14-year-old Annabelle Crisp sets off across the bizarre wasteland to find Silas Monte’s gang, who stole her mother’s voice and destroyed her father, leaving her Only the need for revenge remains.

Since Annabelle’s mother traveled to Earth to care for her ailing mother, she spent her days in New Galveston at school and her evenings at her father’s no-frills diner, with Watson as her only Companion, home kitchen engine and dishwasher. When silence fell, communications and transportation from Earth to the Martian colony ceased, and life seemed to stall ominously until the night Silas Monte and his gang attacked.

I was thirteen when the silence came to Mars, falling on us like choking dust. We don’t talk about those days anymore, and most of those who lived through them have passed away. I’m old now—very old, I like to say—and I’ll be joining them soon. Maybe that’s why I find myself thinking back to those years more often, in the long nights: the fear and loneliness that plagued us all, and the shameful things we did because we were afraid.

Maybe that’s why I’ve also been thinking about old friends and old enemies, thinking that sometimes they’re the same person. Perhaps that is why dear old Watson came to visit me at last, gleaming in the lights and full of his own fascinating stories.

All my life I’ve wanted to write adventure stories, but I’ve always been better at reading than writing. I never believed my imagination was up to the task. Only now, near the end, do I realize that I never had to imagine.

My name is Annabelle Crisp. This is the story of what happened to me, what I did about it, and the consequences.

***

It was early evening and we were closing for Mother Earth. Usually my dad likes to keep this place open until late at night. We’ve been living in silence for almost a year, and in that time it seems more and more people want a warm, bright place to go when night falls. My family would love to offer that place. We specialize in good Southern cooking—beans and rice, kale, pork roast, and more—and our walls are filled with photos of famous cities and landmarks around the globe. It is true that “Silence” imbues these photographs with an elegiac tinge, but this only enhances their appeal.

That night, we closed earlier than usual. The film club is showing movies in the town square, which will lure most people away from us. This works fine for me. I would have liked to visit the square to see it for myself. They’re doing The Lost World again, and while I’ve seen it twice before, I’d love to go again. Arthur Conan Doyle is my favorite author. I re-read Sherlock Holmes with excitement, the spine cracking with my love for it.

Joe Reilly was our last customer of the night. He was despised by many in New Galveston, and he made a habit of coming in when he was most likely to be undisturbed. I’d love to ban him entirely, but my father wouldn’t agree. So I serve him briefly and silently. He wolfed down the food quickly, and then said, “Annabelle, are you closing early tonight?”

“You know we are.”

“Excellent. I think I should let you sort this out.” He put down the money and went out. It’s a relief. Usually he lingers.

I took the dishes to the back, and Father and Watson, our engine, were cleaning. Father had been talking in a low voice, and when I came back he was quiet. He was talking to his mother again. I know it comforts him, but it still hurts to hear it. He only tries to do it when I’m not there, but sometimes I guess he can’t help himself.

Watson is a kitchen engine—a bipedal structure, humanoid, utilitarian and featureless. I called him Watson after a character in a Sherlock Holmes story, but he was little more than a dishwashing routine that my parents overlaid with a cheap personality template (the English butler) to please themselves and their customers. He wasn’t programmed to be the detective’s assistant any more than I was programmed to be the world’s greatest amateur detective. This is a lie I choose to believe.

I was only in the back for a minute so when I got back to the dining area I was surprised to see a man at the counter. He sat hunched over, his hands clasped, studying the tangle of fingers as if trying to unravel the mystery. The hair on his head was long and tousled, blond with the soft pink hue of the Martian lowland desert. He wore a windproof jacket favored by the Nomads, protecting them from the deadly cold of the nights outside the city. A symbol carved into the leather on his right sleeve identified him as a moth—named for a strange, carnivorous moth native to Mars that nests inside the dead. He looked up at me and I was struck by his face, which was unbearably beautiful, as beautiful as a desert. His eyes were pale green and glowed faintly; were it not for the markings on his jacket, I might have mistaken him for a miner. I thought he was at least my father’s age—in his forties—until he spoke and I recognized the youthfulness in his voice.

“I started thinking I was going to die here until someone decided to serve me.”

I was surprised by his rudeness. I didn’t know him, which is unusual in New Galveston, but not impossible, especially if he belongs to one of the desert cults. Despite this, my father and I were respected in the community and generally treated accordingly.

“Sorry, we’re closed.”

“The sign says open.”

“I was trying to turn it off.”

“But you haven’t, so I figured you must be open. I’ll have some black coffee.”

Not knowing what else to do, I turned around and put the water on the stove to boil. It bothers me that this outsider comes in and issues such an order. What bothered me even more was that I obeyed.

For a few minutes I had nothing to do so I leaned against the counter while he sat there watching me. I slid the book under the counter, not wanting to offer the man an opportunity for further conversation. I could hear my father busy in the back, washing the dishes and putting them away. Talk to mom. It was personal: a calm expression of grief, unobtrusive and innocuous; but now the person hears it and I’m embarrassed.

“Who’s behind?” the man said.

“My father. This is his place.”

“Who is he talking to?”

“Our engine,” I said. Lies are easy now. “He’s a dishwasher.”

“Dishwasher, huh? So where’s your mother?”

“Earth.” I felt blood on my face.

“So you help him run the place? He’s got his little girl here to deal with all the wanton scum that comes in through those doors while he’s hiding in the back doing women’s work with the engine in the back?”

“Our customers are not scum. Generally speaking, they are more polite than you.”

“Well, I’m sorry if I offended you.”

“If you’re really sorry, you pick yourself up and walk out that door. As I said, we’re closed. They’re showing a picture in the square tonight, and I want to see it.”

“Little girl, I’m from the desert. I’m tired and I need shelter and some pleasant company. But most of all I need hot coffee. Under this roof, I find I can get all of that at once. I’m not going to leave.”

Water started whizzing behind me and I poured it over the coffee grounds. “Well, I’m not very friendly,” I said.

“Yeah, you’ve made it very clear. What the hell are you looking for?”

“They’re showing The Lost World.” As I said this, I felt an unwelcome childish excitement as I pictured those beautiful dinosaurs in my head.

He smiled and shook his head.

I wish I hadn’t answered him. Now I am ashamed and angry. As I pour the coffee into his mug, I let a lot of coffee grounds slide in with it.

He said: “Haven’t you seen it a hundred times? Won’t you see it a hundred times again? There will be no more pictures from home now. What we get is what we get.”

I didn’t answer him. It’s not something I hadn’t thought of before. But I still insist that maybe we can make new photos somehow. finally. I insist that the months of disruption to our normal lives will soon be corrected. All it takes is hard work, reason, and mostly patience. The world works according to a long-standing order, and as soon as people start functioning normally again, it will return to normal.

I wouldn’t bother arguing that, though. He drank a cup of coffee, and as far as I could tell, my obligations to him were over. “Ten cents,” I said.

He held the cup with dirty hands, closed his eyes, and breathed in the taste of the cup. “It doesn’t make any sense,” he said.

I feel like my patience is about to collapse. “That means you owe us ten bucks! You can’t just break in here when we’re closing and not pay!”

He gently put down his cup, and said, “Force? Little girl, calm down. When I am ready to pay you, I will pay you. If you think that money no longer means anything, then you are better than I imagined more naively. The old things don’t matter anymore. Don’t you understand?

Behind me I heard the kitchen door open, and my father said, “Bell, are you shouting? What’s going on here?

Father looked tired. In those days, he always did. He was short and thin even in good health, but in the months since the silence began he looked almost scrawny. The hair on the top of his head has thinned to only a few gray strands. His clothes were wet from the dishwashing water and hung loosely around him. His face was worn out. He turned into an old man in front of me. Whenever I see him, I feel a bewildering sense of sadness and terror.

“I told the guy to pay for the coffee, but he wouldn’t do it.”

He puts his hand on my shoulder. “Annabelle, it’s just coffee,” he whispered in my ear. “My daughter is wayward. That’s why I keep my honesty,” he told the dusty scavengers across the counter. I had the creeps; he had no right to apologize for me. Not so when I’m right. He smiles at the man. If you don’t know him, this might seem sincere.

“Your sign says open,” the man said, as if my father had somehow challenged him.

“Of course. We’re coming to an end, but you’re welcome to stay and finish.”

“Why don’t you go ahead and turn it off.”

“I don’t mind being open a little longer. Honestly, you’re doing me a favor. Anyway, I’ve got work to do here. And I don’t mind having company.” Father walked around the counter with a broom Walk in and get ready to clean the main floor.

“I said turn off the sign.”

The father stopped and turned to look at the man. Another surge of anger ran through my blood. I’ve always had a bad temper and it got me in trouble sometimes, but some people let it out. Some people just need to be punched in the face.

I want my father to put him in his place. I want him to grab the intruder by the dirty collar, drag him kicking and screaming across the restaurant, and throw him outside. I want him to black out those beautiful eyes. But it’s not his way. He has always been a gentle man. He likes to be quiet and he likes to be polite. I used to wonder, ten years ago, what it was that made such a fragile man volunteer to become one of the first permanent colonists on Mars. Brave people do such things. My father was not brave.

mother is.

“Okay,” he said. He glanced at me, then back at the man. “Keep calm. I’ll turn it off.”

“I’m calm, old man. As long as you do what I say, I’ll stay that way.”

My father walked up to the sign hanging in the window, and as he did so, I calculated the odds against the intruder. I had boiling water on hand, but I had to take two or three steps to reach it, then turn around and throw it at him. This leaves him with too much time. We take the knives to the back to clean them; the fryer is off and the oil is cooling. Watson stayed behind, scrubbing dishes, as useless as a potted plant. So I gave him a hard look, hoping his imagination would be strong enough to explain in my mind the magnitude of the disaster I had brought him.

When he looked back at me, his expression was blank, indicating that this was not the case.

Father tugged at the string on the neon sign. It crackled and went off. He flicked a switch, and half the interior lights went out, leaving only the kitchen on and a few emergency lights in the dining area. He kept quiet as he walked back around the counter until he was standing next to me. “There,” he said. “We’re closed. Annabelle, go back to the kitchen.”

“You stay where you are, Annabelle,” the man said.

“Do as I say. Now.”

I began to obey, despite every urge to tell me to stay.

The man slapped his hands on the countertop. “Aren’t you ten? Aren’t you—”

My father also raised his voice, but before I could understand what he was saying, the stranger drew a pistol from his belt and hid it under his coat, and his movements were graceful and skilled, and I would not think it was a person so rude. people. He flipped once in the air and grabbed it by the barrel before hitting my dad hard in the temple, throwing him on the counter like a sack of oats. Dad slipped and fell; I tried to pick him up, but he was too heavy. The intruder tightened his grip on the gun again, the transition too fast for me to follow, its open end pointing at my face.

“Now damn it, you stay there!”

I was terrified. I didn’t move. I watched my father bleed quietly on the floor, which was dirty from our footprints and the sand blown from outside. He was as still as a moon in the sky.

Tagged 1:1 spin-orbit resonance, Earth, exoplanet, Mercury, Science fiction