Build our personal library and the books we leave behind

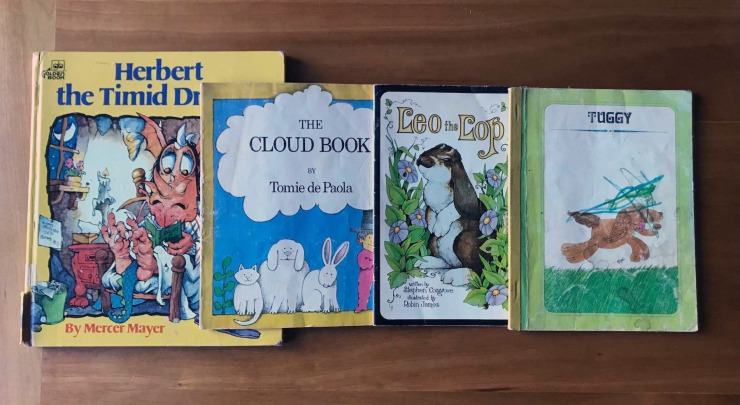

The book I’ve owned the longest has zero prestige, zero coolness, zero popularity. It’s not an old version of my beloved “Castle Lear,” or Mercer Meyer’s “Herbert the Cowardly Dragon.” It was an early reader named Tuggy, who unexpectedly scrawled “Bailey Hill High School” in crayon on the inside cover.

Tuggy is a book designed to teach vocabulary to young readers. I don’t remember it being part of my learning to read process, except that I still have it on my shelf, tattered and ink-stained, with other old, battered children’s books, including Lop Rabbit, and Tommy DePaula’s book The Clouds, thanks to which I used to know many more cloud names than I do now.

I have no real reason to own these books. They rarely talked about me, other than that – like a lot of kids – I loved stories about animals and the world around me. They’re dirty replicas, not the sort of thing people collect. I have no children to pass on to them. You could call them sentimental, unnecessary, even confusing. But they make sense to me. They are part of my story. At the end of the day, isn’t that why we keep anything—especially books?

I’ve been thinking about personal libraries since someone recently wrote an article against them in a high-profile paper. It seemed like an inexplicable position for a bookish person like a total troll, and at first I resented myself for taking the bait. But then I sat down and looked at the wall of books at home – to be honest, there were several, but one of them was the main wall, all the books that me or my partner had actually read – and thought about what was on that shelf, what isn’t there, and how what got there.

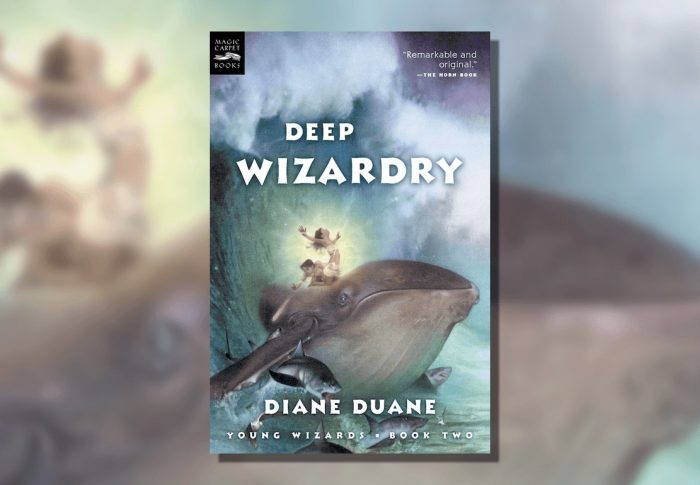

My first library was a bookcase with a shelf of books propped up on cinder blocks – books I received as a child; books I stole from my parents’ shelves and made myself; I would never know where they come from. I’m so obsessed with libraries that I put little pieces of masking tape on the spine of each library, each with a letter and number on it, just like in a real library. This was deliberate, as any additions to the library would not fit into the numbering system, but I was in elementary school at the time. Foresight is not my strong suit.

When I was younger, I kept every book, even those watered-down Tolkien fantasies that I didn’t really like. Since then, I’ve moved countless times; spent four years in a dorm with nowhere to store more books than absolutely necessary; lived briefly overseas and made tough choices about which books to bring home; books on shelves, in milk crates, apple crates, bookshelves handed down from neighbors or relatives; shelves of all shapes and sizes at IKEA; It’s the perfect size for my craft book, fairy tale book, reference book, and folklore. This is where I keep my read and unread books side by side, a collection of inspirations, wishes, and ideas that I often reorganize.

I don’t keep everything anymore. The first time I got rid of books, I was a college student with my first bookstore job, and I was disappointed by a much-hyped Nicholson Baker book that, as far as I could tell, did absolutely nothing. I don’t want it. It was a crazy new feeling to get out of a book—so crazy at the time that I remembered it years later.

I don’t remember what I did with it, but I don’t own the book anymore.

What’s gone makes up your story as much as what remains. Sometimes, when I look at my bookshelf, all I see are books I didn’t keep: Mystery of Solitaire first edition, which I never had time to read so let go; I loved it so much but will never reread it The second and third books in a series of books; I’ve written books in various publishing jobs, but never had one. They are ghost books, hovering over the edges of the shelves, whispering among the pages I keep.

I started keeping reading lists as a way of keeping track of all the books I’d read but didn’t keep, but they didn’t offer the same feeling as actually viewing books: being able to pull them off the wall, flip through them, and remember yes What attracted me or kept them in my memory. Some old paperbacks have the month and year I finished them written in pencil on the back. Very few have gift inscriptions; some are signed, most are from events I’ve hosted. There is one book that has moved me for twenty years, but I absolutely hate it. I hate this book. It’s a story about an indie rock band in the ’90s, but not a word of it sounds real. But I keep it because I read it and hated it, my musician friends read it and hated it, and the memoryThe book I’ve owned the longest has no prestige, coolness, or popularity. It’s not an old version of my beloved “Castle Lear” or Mercer Meyer’s “Herbert the Cowardly Dragon.” It’s an early reader named Tuggy, on which someone unexpectedly scrawled “Bailey Hill High School” in crayon on the inside cover.

Tuggy is a book designed to teach vocabulary to young readers. I don’t remember it being part of my learning-to-read process, but I still have it on my shelf, tattered and ink-stained, alongside other old, battered children’s books, such as “Lop Rabbit” and Tommy DePaula’s “The Clouds,” which helped me learn many cloud names.

I have no real reason to own these books. They rarely featured me, other than that – like a lot of kids – I loved stories about animals and the world around me. They’re worn-out copies, not the sort of thing people collect. I have no children to pass them on to. You could call them sentimental, unnecessary, even confusing. But they make sense to me. They are part of my story. At the end of the day, isn’t that why we keep anything—especially books?

I’ve been thinking about personal libraries since someone recently wrote an article against them in a high-profile paper. It seemed like an inexplicable position for a bookish person like me, and at first, I resented myself for taking the bait. But then I looked at the wall of books at home – to be honest, there were several, but one of them was the main wall, all the books that my partner and I had actually read – and thought about what was on that shelf, what wasn’t there, and how it got there.

My first library was a bookcase with a shelf of books propped up on cinder blocks – books I received as a child; books I stole from my parents’ shelves and made myself; I would never know where they come from. I’m so obsessed with libraries that I put little pieces of masking tape on the spine of each library, each with a letter and number, just like in a real library. This was deliberate, as any additions to the library would not fit into the numbering system, but I was in elementary school at the time. Foresight is not my strong suit.

When I was younger, I kept every book, even those watered-down Tolkien fantasies that I didn’t really like. Since then, I’ve moved countless times; spent four years in a dorm with nowhere to store more books than absolutely necessary; lived briefly overseas and made tough choices about which books to bring home; stored books on shelves, in milk crates, apple crates, bookshelves handed down from neighbors or relatives; and shelves of all shapes and sizes from IKEA. They’re the perfect size for my craft book, fairy tale book, reference book, and folklore. This is where I keep my read and unread books side by side, a collection of inspirations, wishes, and ideas that I often reorganize.

I don’t keep everything anymore. The first time I got rid of books, I was a college student with my first bookstore job, and I was disappointed by a much-hyped Nicholson Baker book that, as far as I could tell, did absolutely nothing. I don’t want it. It was a crazy new feeling to get rid of a book—so crazy at the time that I remembered it years later.

I don’t remember what I did with it, but I don’t own the book anymore.

What’s gone makes up your story as much as what remains. Sometimes, when I look at my bookshelf, all I see are books I didn’t keep: a first edition of “Mystery of Solitaire,” which I never had time to read so I let go; the second and third books in a series; books I’ve written in various publishing jobs but never owned. They’re ghost books, hovering over the edges of the shelves, whispering among the pages I keep.

I started keeping reading lists as a way of tracking all the books I’ve read but didn’t keep, but it doesn’t offer the same feeling as actually seeing the books: being able to pull them off the wall, flip through them, and remember what attracted me to them or kept them in my memory. Some old paperbacks have the month and year I finished them written in pencil on the back. Very few have gift inscriptions; some are signed, most are from events I’ve hosted. There is one book that has moved me for twenty years, but I absolutely hate it. It’s a story about an indie rock band in the ’90s, but not a word of it sounds real. But I keep it because I read it and hated it, my musician friends read it and hated it, and the memory

Tagged character preferences, complexity, do-gooders, morality, paladins